V. Angelis suis Deus mandavit de te.

R. Ut custodiant te in omnibus viis tuis.

[For he hath given his angels charge over thee; To keep thee in all thy ways.]

It is undeniable that the Normans had an effect on England, and later, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland too. Sometimes this was direct, for example the Norman Conquest (1066), at other times, such as David I of Scotland’s attempts to mitigate the power of the Scottish nobles by inviting Norman nobles to his court this was less direct. Looking at Ireland in particular, the Normans have been labelled as “more Irish than the Irish themselves”.[1] Wherever the Normans went, be it Britain, Sicily, France, Jerusalem, they left their mark, they were the “Romans of the Middle Ages”.

Perhaps it is a little too easy to generalise in history. Historians use the terms “Norman”, “Anglo-Saxon”, “Tudor”, “Stuart” and so on to neatly parcel up periods of history but history isn’t neat at all. Moreover, one thing the Normans did very well is integrate and adopt the customs of the areas they conquered and/or dwelled in. So less than a century after the Conquest there was to a large extent an England not under a “Norman yoke” but its own distinct kingdom. Likewise, in Sicily the Normans rapidly colonised and integrated with other cultures – Jews, Muslims, Byzantines. And of course, in Normandy, France they became “Catholic Vikings” and took on the language and culture of the Franks.

If the Normans were “Catholic Vikings” like Saint Olaf II of Norway (pictured) then that’s not so bad compared to secular modernity. To admit where one is from truly means to know oneself and step over any unfair criticism to the contrary, especially if that is nefarious in nature. For example, the Borders, between England and Scotland were a notorious region, a land of brigands and thieves. To overcome that and move upwards proud of your ancestry is a necessary first step. So, to admit the Normans, the Borderers, the English Privateers, the Merchant Navy and so on opens our eyes to a tradition of a seafaring nation that otherwise would be consigned to the dustbin of history for its perceived offensiveness. We at least have as our pilot and our guide one to whom we can confidently offer up the rudder of our lives.

It is hard to tell how much of the “Norman Spirit” remains within the English today. Any ability to integrate our culture has failed because we are living in a cultureless time – the Kali Yuga. Though that would be to get ahead of ourselves. One must first ask oneself the question, why was I born? And as a corollary what is my purpose? Before trying to discern why this specific time and this specific place. Logres over at Gornahoor quoting Tennyson wrote: “kind hearts are more than coronets, and simple faith more than Norman blood; Heaven’s Truth being additive, can simply add that perfection is both the attainment of Norman blood, and the purity of simple faith with kind hearts, crowned with the corona.” Today we have too many “kind hearts” and not enough “Norman blood” – blood equating to the Human I or the Person – who they are incommunicably, uniquely, unrepeatably, indivisibly and distinctly. To quote Saint Bernard, as I did five years ago when I began this journey:

“[Just as] an eye raging in anger sees nothing mercifully, … one that is filled with a flood of womanly weakness does not see straight.”

Too much mercy and sentimentalism has led away from Justice and Truth.

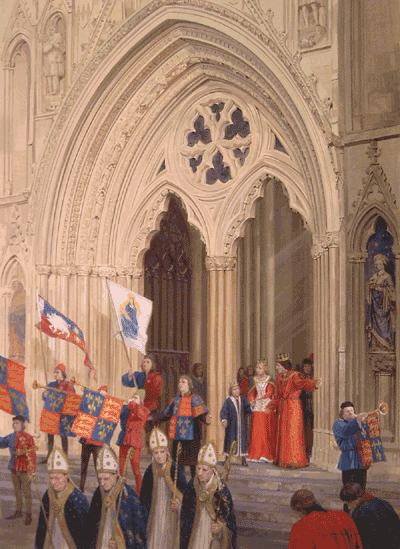

Perhaps I am being sentimental when I declare an attachment to this past? Or this view of the past? On the other hand, looking at the spiritual currents of history as others have done we see that the last traditional civilisation closest to us in space and time is that of Western Europe in the High Middle Ages (1000-1250). Beginning with the Renaissance of the twelfth century, which built upon the Carolingian Renaissance developments were made socially, politically, economically, and an intellectual revitalisation took place with strong philosophical and scientific roots. New technological discoveries allowed the development of Gothic architecture synonymous with the period. This was a development of Norman architecture, with its characteristic Romanesque rounded arches (particularly over windows and doorways) and especially massive proportions compared to other regional variations of the style.[2] In addition, even before the Conquest Norman nobles and bishops had been influencing English (late Anglo-Saxon) architecture.

Growing up among the physical ruins of great abbeys, and the cultural ruins of the Church of England made me long for something stable. It is to an “unmoving” tradition that I wish to anchor myself, and, actualise within myself. Living where I have done for the last five years has given me the opportunity to do just that. When the Normans arrived here, they imposed the new king’s authority on the rebellious Anglo-Scandinavian city. Razing most of the city and rebuilding it in their image, the Normans laid the foundations for the entire medieval period. Much of this survives today; the Minster (Northern Europe’s largest Gothic cathedral), the city walls, some churches but sadly not many of the religious houses.

The Medieval period in England is bracketed by the dates 1066-1485; the Norman Conquest to the death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth. As a historian I might see this differently to others. What strikes me is the replacement or “Normanisation” of the nobility by force and influence (which began before 1066) and then the death of nobility in the series of wars known as the War of the Roses where the flower of English chivalry died. They died physically but lived on in the work of Sir Thomas Malory (d. 1471), Le Morte d’Arthur (1485) who was himself a combatant in these “wars”, in which he supported both sides at different times.[3] Interestingly the Norman period within the larger Medieval period ends in 1154, the year Stephen, King of England and his relative Saint William of York died.

St. William, whose statue above the eponymous college is fantastically detailed, is someone I don’t know very well. He was friends with Roger II, King of Sicily – a fellow Norman. He was canonised in 1226 by Pope Honorius III who also approved the then newly formed Dominican and Franciscan orders. St. William struggled against another order, the Cistercians between 1147 and 1153 to have his archiepiscopal see restored to him – which didn’t come about until Eugene III (one of St. Bernard’s spiritual sons) and his rival Henry Murdac died. He made peace with the community at Fountains Abbey after his re-election on 20th December 1153 though he himself died shortly after his return (8th June 1154), allegedly poisoned with the chalice he used to celebrate Mass.

Looking ahead to May, the month of Mary, and sharing a baptismal date with the feast of Saint Augustine of Canterbury, I will have been a practicing Catholic for five years. I believe I have come a long way in that time, and though born on the Sabbath day, still have far to go. To summarise, by grounding myself in the exoteric tradition of my forbears I hope to be elevated in their esoteric tradition too. This vital tradition, this spiritual current mixed with those of a Germanic/Scandinavian mode (Beowulf for example). I will leave this for another article in the future. Suffice it to say that the Normans by their Conquest connected or redirected England to France and to Rome rather than Scandinavia, and insular Christianity – which had past to a certain extent with the changes of keeping Easter after the Roman fashion in the seventh century – bringing with it the Matters of Britain, France and Rome, as well as opening it to Cistercian and Scholastic thought (see St. Bernard, Saint Thomas et al).

[1] Here I could go on to talk about the influence the ‘Celts’ had on the Anglo-Saxons and then the Normans, though I think I will save that for a later article where I will touch on the Grail Legend, Arthurian kingship, Jacobites, the ‘aristocracy of America’, and it’s creation myths.

[2] See for example, Durham Cathedral, Southwell Minster, and Winchester Cathedral.

[3] Written in prison, Le Morte d’Arthur was first published in 1485 at the end of the medieval English era by William Caxton, who changed its title from the original The Whole Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table (The Hoole Book of Kyng Arthur and of His Noble Knyghtes of The Rounde Table).