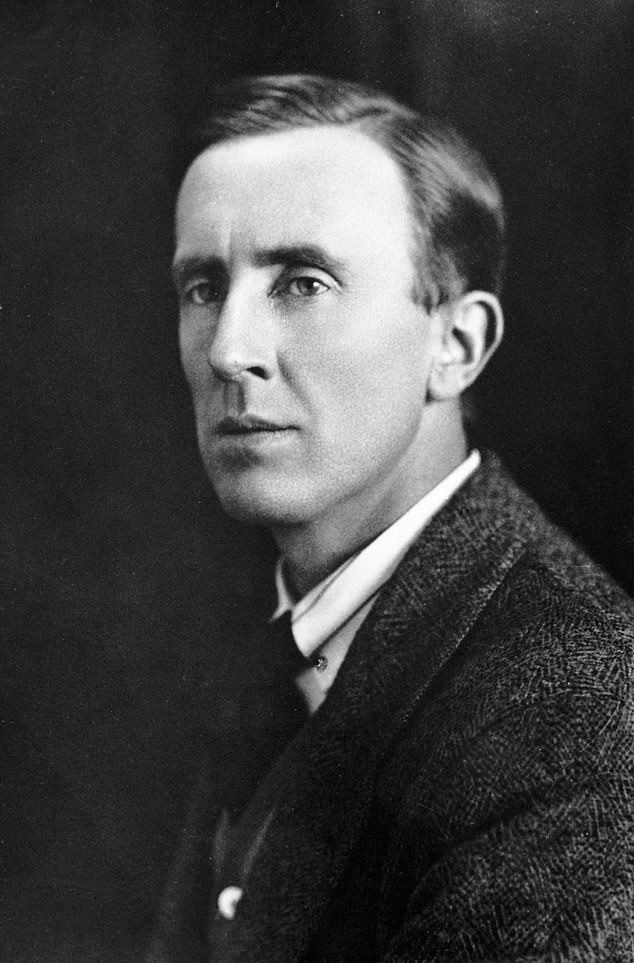

JRR Tolkien grew up with the Catholic Faith. His mother, a convert and widow, gave to him and his brother this unparalleled gift. His childhood was spent with the Fathers of the Brompton Oratory in London. His closeness to the Blessed Sacrament was to remain a constant throughout his life, he attended Holy Mass and received Holy Communion daily. It is in this we see where he experienced the graces that were to be key to his work and are evident in it.

Craig Bernthal makes the case for Tolkien’s sacramental vision in the eponymous book published recently.[1] He argues that Tolkien, in writing the Lord of the Rings (and the associated literature), has created a ‘holy’ work. Tolkien himself considered that he wrote with inspiration, perhaps even divine inspiration.[2] It might be the case that Tolkien’s work is divinely inspired, he lived a life of sanctity, and there is cause for his canonisation. Yet what I am interested in is how he came to imagine what he did. He wrote “the stories arose in my mind as given things”.[3] What does that mean?

I did not grow up as a Roman Catholic. Though now I am a member of the Church, and I happen to live close to an Oratory. I attend Mass as often as I can and receive Communion in like manner. What arose in my mind was the example of Tolkien, who as an Inkling has connections to rediscovering the Imagination as a creative force. Well we know nothing comes out of nowhere, so where did these stories come from and how can we replicate that? One could say it is only possible to find ‘new’ things by writing them and voicing one’s perspective. Which is a unique because it is uniquely yours.

For Tolkien, he wrote the Lord of the Rings as a home for the languages he had created. We know that words are symbolic of the essence of a created being or object. Adam named the beasts therefore he knew their essences. Bernthal points out, using Tolkien’s poem Mythopoeia, that Tolkien thought through speech we breath the world into life.[4] The creation of Arda in the Silmarillion is done so through music and song. And the Elves, like Adam, name the stars ‘el’ or God. We can link this to the work of Saint Thomas Aquinas and Aristotle, and even Plato, who Tolkien was conversant with along with Saint Augustine. Tolkien’s mythopoetic observations have been noted for their similarity to the Logos which acts as both “the […] language of nature” spoken into being by God, and “a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM”.[5]

I believe Tolkien was ‘remembering’ Truths that had been forgotten. It would be worth cultivating a life similar to his in order to know how to proceed. There is plenty of material to work with, and signs to show us the way, all it takes is effort to do the exercises. We have mentioned this before, and it has been mentioned by others before too. Tolkien was evidently able to return to a higher state of consciousness,[6] to wit “the chief practical objectives are mastery of the sexual centre, and the training of the emotional centre.”[7] Spending an hour in front of the Blessed Sacrament each day will help us to with this internal war. Venerable Fulton Sheen declared this more necessary than the external struggle for without it we will not have the moral courage to salute the same flag that others have fought and died for.

[1] Craig Bernthal, Tokien’s Sacramental Vision: Discerning the Holy in Middle Earth (Angelico Press, 2014).

[2] Bernthal, Tokien’s Sacramental Vision, p. 46.

[3] Bernthal, Tokien’s Sacramental Vision, p. 45 n. 54.

[4] Bernthal, Tokien’s Sacramental Vision, p. 59.

[5] Lisa Coutras, Tolkien’s Theology of Beauty: Majesty, Splendor, and Transcendence in Middle-earth (Springer, 2016). Verlyn Flieger, Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World (Kent State University Press, 2002). The last from S. T. Coleridge’s famous declaration in Biographia Literaria.

[6] “new source of moral energy”

[7] Boris Mouravieff, Gnosis, p. 229.